When the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the right of the Westboro Baptist Church to picket the funerals of U.S. servicemen and women, one case that came up was that of Falwell v. Flynt. Here’s a bit of a refresher for those who don’t remember the details:

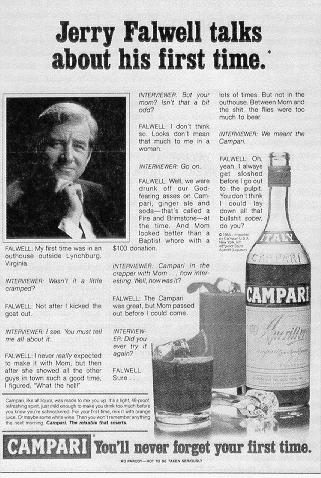

In 1983 the Reverend Jerry Falwell was in Washington, D.C., for a news conference when a reporter rushed up to him carrying the November 1983 issue of Hustler magazine and asked, “Reverend Falwell, have you seen this?” The reporter was referring to a crude parody of a Campari ad that portrayed a drunken Falwell losing his virginity to his mother in an outhouse. Under the ad was the statement, “Ad parody—not to be taken seriously.” The Falwell ad parodied a series of Campari ads that featured celebrities using sexually suggestive language to describe the “first time” they had tasted Campari.

In 1983 the Reverend Jerry Falwell was in Washington, D.C., for a news conference when a reporter rushed up to him carrying the November 1983 issue of Hustler magazine and asked, “Reverend Falwell, have you seen this?” The reporter was referring to a crude parody of a Campari ad that portrayed a drunken Falwell losing his virginity to his mother in an outhouse. Under the ad was the statement, “Ad parody—not to be taken seriously.” The Falwell ad parodied a series of Campari ads that featured celebrities using sexually suggestive language to describe the “first time” they had tasted Campari.

Falwell was outraged by the ad, not only because it insulted him but also because it attacked his mother. Describing the ad as “the most hurtful, damaging, despicable, low-type, personal attack that I can imagine one human being can inflict upon another,” he filed suit against famed publisher and pornographer Larry Flynt, asking for $45 million for libel (publishing false and defamatory statements about him), the improper use of his name and picture in the ad, and the infliction of “severe emotional anguish and distress.”

In the initial trial, the jury did not award Falwell damages for injury to his reputation because, they said, no reasonable person would believe the outrageous claims in the parody ad. The judge dismissed the portion of the suit dealing with the improper use of Falwell’s name and picture, ruling that as a public figure Falwell could not prevent the use of his name and image for noncommercial purposes.

However, the jury awarded him $200,000 in damages for the intentional infliction of emotional distress because it was clear that Flynt wanted to hurt Falwell.

After an appellate court upheld the verdict, Flynt appealed the case to the U.S. Supreme Court. Although Flynt was known for his outrageous behavior and was not popular with mainstream publishers, numerous groups advocating freedom of the press filed amicus briefs in support of him; they included several newspaper owners, press associations, and the Association of American Editorial Cartoonists. Also supporting Flynt was HBO, which was looking to protect the stand-up comics featured on the cable network.

On February 24, 1988, in an 8–0 vote, the Supreme Court overturned the lower court’s verdict, ruling that the courts could not protect a public figure from emotional distress, even from “speech that is patently offensive and intended to inflict emotional injury.”

The Court ruled that given a choice between protecting a public figure from emotional distress and protecting free speech rights, it would support free speech.

Chief Justice William Rehnquist acknowledged that the ad was “doubtless gross and repugnant in the eyes of most,” but said that political cartoons often go beyond the limits of good manners and taste. He saw no way to distinguish between proper and improper satire or between fair and unfair comment and criticism. The Court ruled that the only way a public figure or official could win a decision for intentional infliction of emotional distress would be if false statements had been made with knowledge that the “statement was false or reckless disregard as to whether it was true.”

This was the central point of the Flynt decision—that even something mean-spirited and cruel is still legitimate opinion and commentary, as long as it is a statement of opinion and not a statement of fact. Flynt explained the significance of the decision from the publisher’s point of view in an interview:

Had those decisions been allowed to stand, it would have meant that you would no longer need to prove libel to collect damages. All you would have to do is prove intentional infliction of emotional distress. Well, you know, any political cartoonist or editorial writer wants to inflict emotional distress. That’s their business.

In a strange ending to this case, Falwell, who passed away on May 15, 2007, and Flynt developed a relatively civil relationship in recent years, appearing in debates and on television together. On one occasion, Falwell even accepted an airplane ride home from Flynt following a joint speaking engagement.

The conflict between Larry Flynt and Jerry Falwell highlights the central conflicts in American media law:

- How do you protect both the rights of individuals and those of the press?

- Is the press protected even when it is “gross and repugnant in the eyes of most?”

- When can the media be punished for stepping over the line?

- Do individuals have a right to control how a sometimes hostile press portrays them?

When the movie The People versus Larry Flynt was released, Flynt and the Reverend Jerry Falwell appeared together on CNN’s Larry King Live.

Pingback: Link Ch. 13 – Snyder v. Phelps | Living in a Media World