This week I’m at the Western Social Science Association annual conference. I’m giving a presentation on the explosion of stories in the news media about sexual harassment by high profile men, especially those in the media industry. Rather than writing a conventional conference paper, I will have series of blog posts covering my topic over the next day or so.

Resetting the Agenda:

How Sexual Harassment & Assault

Became The Story of 2017 – Part 3

So where did it really start?

So if this story of sexual harassment didn’t start with Harvey Weinstein, when did it? The media’s interest and concern about sexual misconduct by men could also date back two years when news first started breaking about Bill O’Reilly paying out multiple private settlements and being forced out at Fox News for his behavior.

Or it could be 27 years ago when Anita Hill testified about Clarence Thomas’s behavior toward her at his Supreme Court confirmation hearings. But while Ms. Hill brought a lot of attention toward the issue during those hearings, her testimony didn’t stop Thomas’s confirmation.

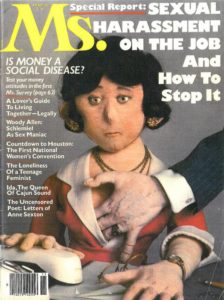

The cover story of the November 1977 issue of Ms. magazine was about sexual harassment (New York Times

But perhaps one of the best dates to choose would be just over 40 years when, according to the New York Times, Ms. magazine published their first cover story on sexual harassment in 1977. As journalist Jessica Bennett points out, “Understanding the sensitivity of the topic, the editors used puppets for the cover image — a male hand reaching into a woman’s blouse — rather than a photograph. It was banned from some supermarkets nonetheless.” She goes on to note that sexual harassment was not yet a legal concept and was just entering into our vocabulary.

Despite being more than 40 years old now, the story is still disturbingly fresh:

“It describes an executive assistant who quit after her boss asked for oral sex; a student who dropped out after being assaulted by her adviser; a black medical administrator whose white supervisor asked if the women in her neighborhood were prostitutes — and, subsequently, if she would have group sex with him and several colleagues.

“Citing a survey in which 88 percent of women said they were harassed at work, the author said the problem permeated almost every profession, but was particularly pernicious ‘in the supposedly glamorous profession of acting,’ in which Hollywood’s casting couch remained a ‘strong convention.’”

The Story After Harvey

It would be impossible in anything under a New Yorker long read to try to talk exhaustively about all the men who have been accused and fired since Harvey Weinstein was forced out of the company that bears his name.

There doesn’t seem to be any limits to where these stories emerged from. While there had clearly been a culture at Fox News that tolerated bad behavior from evening talk show host Bill O’Reilly and from network founder Roger Ailes, there were also journalists, executives and performers from CNN, NPR, PBS, the New York Times, the left-leaning online news source Vox, streaming giant Netflix, and NBC’s news, entertainment and reality programming.

There are certain commonalities that emerge from these stories:

Someone wants to cover for the offenders

NPR chief executive Jarl Mohn went on medical leave from the non-commercial radio company in November of 2017, claiming blood pressure problems. But he also may have taken leave for how he handled charges against editor Mike Oreskes.

There are accussations that when two sets of charges came forward independently about Oreskes, Mohn worked to bury them. Mohn used a variety of arguments for why he did not discuss all the charges against Oreskes. Among these were:

- The events happened a long time ago at a different news organization (NYT, 20 years ago).

- The woman in one of the cases wanted to protect her privacy and did not want her case reported publically.

People make excuses for the abuser and the abuser makes a mild apology.

Television host Charlie Rose, who had a long-running interview program on PBS as well as reporting for CBS and Bloomberg TV faces charges from at least eight women that he “made unwanted sexual advances toward them, including lewd phone calls, walking around naked in their presence, or groping their breasts, buttocks or genital areas.”

Rose’s comments seemed typical from the flood of stories:

“In my 45 years in journalism, I have prided myself on being an advocate for the careers of the women with whom I have worked. Nevertheless, in the past few days, claims have been made about my behavior toward some former female colleagues.

“It is essential that these women know I hear them and that I deeply apologize for my inappropriate behavior. I am greatly embarrassed. I have behaved insensitively at times, and I accept responsibility for that, though I do not believe that all of these allegations are accurate. I always felt that I was pursuing shared feelings, even though I now realize I was mistaken.

“I have learned a great deal as a result of these events, and I hope others will too. All of us, including med, are coming to a newer and deeper recognition of the pain caused by conduct in the past, and have come to a profound new respect for women and their lives.”

Here is where we see the next step of the story. PBS and Bloomberg TV stopped distributing Rose’s show and CBS suspended him.

Another common element – stories about these men had been surfacing for years but they hadn’t gotten attention.

When assistant Kyle Godfrey-Ryan complained to Rose’s long-time executive producer, she said her response was “That’s just Charlie being Charlie.”

Accusers didn’t want to talk about it

A Washington Post contributor said she had tried to report on a pair of cases involving Rose for the blog Jezebel in 2010, but she was unable to get confirmation. She started digging back into it aggressively when the Harvey Weinstein story started breaking.

Rose had been divorced since 1980, and the late Radar magazine called Rose a “toxic bachelor” in 2007 and reported charges of him groping an unnamed woman. Rose’s attorney at the time demanded a retraction from Radar but the publication refused.

This was also a story where there was a serious disparity in power. These young women would tolerate abuse because they wanted jobs. The women also say they didn’t want to admit to themselves how they were being treated so they pretended it hadn’t happened.

One of the women told the Post, “Remaining silent allowed me to continue denying what had occurred. It was a state of denial that I wrote to him asking about the job.”

Conclusion: A Story Framed by Critical Theory

When I wrote the abstract to propose this paper several months ago, I assumed I was writing a paper about agenda setting, as I discussed at the beginning of the paper. But I no longer think that’s the central issue here. (I’m sure there is some level of agenda setting going on, but it would take more evidence than I have here to document it.)

I would suggest instead, that this is a story of women finally speaking up and forcing the media to listen to them; to put their (justifiable) fears behind them; to hold their abusers accountable.

As I wrote at the beginning:

Critical theory can be summarized with the following principles:

- There are serious problems that people suffer that come from exploitation and the division of labor.

- People are treated as “things” to be used rather than individuals who have value.

- You can’t make sense out of ideas and events if you take them out of their historical context.

- Society is coming to be dominated by a culture industry (what we might call the mass media) that takes cultural ideas, turns them into commodities, and sells them in a way to make the maximum amount of money. This separates ideas from the people who produce them.

- You cannot separate facts from the values attached to them and the circumstances from which these facts emerged.

A commentary written in December 2017 by Manhole Dargis, the co-chief film critic for the New York Times, argues that the physical abuse of women started to get talked about more when the financial and status abuse of women in the film industry broke in 2014 when the computers at Sony were hacked and large numbers of documents with business notes were disgorged.

The files showed how much more men got paid than women in movies, and how women were often not even considered as candidates to direct major films.

Dargis discusses the institutional sexism that has long been in the movie industry by quoting from Molly Haskell’s seminal 1974 book on sexism in Hollywood, From Reverance to Rape: The Treatment of Women in the Movies. Haskell writes:

“Through the myths of subjection and sacrifice that were its fictional currency and the machinations of its moguls in the front offices, the film industry maneuvered to keep women in their place; and yet these very myths and this machinery catapulted women into spheres of power beyond the wildest dreams of most of their sex.”

And it’s this combination that we see coming through all of the comments from women in Hollywood today.

Dargis says that for herself she battles with how much attention she has to give to the issues of sexism in the movies when she confronts just wanting to enjoy a great movie:

“It can be exhausting. Sometimes, you just want to watch a movie, not keep a running inventory of each affront, every offensive line or beat. Did women direct, write, produce, star? Does the female lead have anything of interest to say? Why is she taking off her underwear for the lovemaking scene while the guy keeps his on? Why is her breast showing? Why is she smiling (always smiling)? Why is she a hooker? Or dead? Is she merely there, kind of like the dog or a pricey lamp, so she can suggest that the hero is also an Everyman?”

Sexual Harassment & Assault: