A couple of months ago I saw the following Tweet from my online friend Candice Roberts:

Given that Dr. Roberts knows much more on this subject than I do, I invited her to do a guest blog post, which she so kindly sent!

Dr. Candice Roberts is a media studies researcher and Assistant Professor of Communication who is interested in popular and consumer culture, narratives of identity, and queer theory. Feel free to @ her (@popmediaprof on Twitter).

An April 2018 headline from Autostraddle, an arts and culture website run by and featuring content for lesbian and queer women, highlights “53 Queer TV Shows to Stream on Netflix.” A few years ago 53 different queer-themed television shows on any single, media platform would have seemed implausible if not impossible. Now this list not only exists but is populated with widely recognizable hits such Orange is the New Black and Glee as well as lesser-known shows like The Shannara Chronicles and CW’s Legends of Tomorrow; it also includes several of Netflix’s own original programs like Everything Sucks!, One Day at a Time, Gypsy, and Sense8— the latter of which spurred a major fan campaign when it was cancelled after two seasons. (Netflix ultimately recognized fan dismay and promised Sense8 viewers a two-hour series finale as a consolation.)

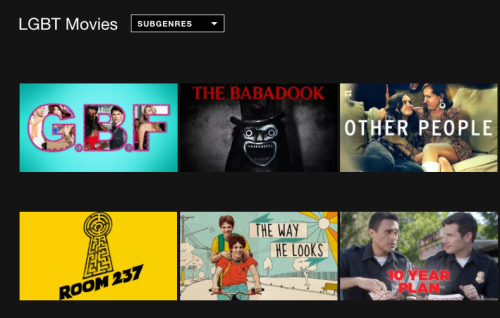

Netflix and streaming-competitor Hulu introduced LGBT sections and genre tags in 2012. Despite Hulu’s blog post concerning the category launch, the rollouts on both sites happened relatively quietly, with consumers discovering the new additions on their own and most of the publicity coming via word of mouth.

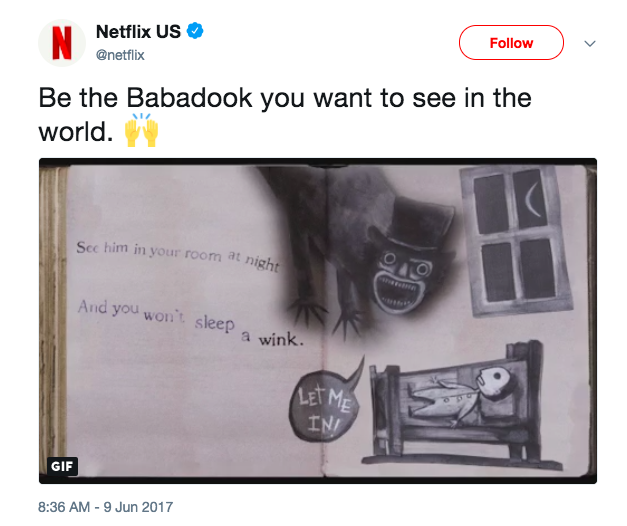

An algorithmic snafu in 2016, however, drew more attention to Netflix’s LGBT movies genre. When Tumblr user Taco-bell-ray posted a screenshot of his Netflix interface showing horror film The Babadook represented within the LGBT Movies category, the Internet did what it does best: meme’d this mistake for all it’s worth.

By the summer of 2017, the Gay Babadook had spread. While Netflix did not comment directly on the incident, the official Twitter account hinted at the company’s social media savvy and corporate awareness. The erroneous sorting of The Babadookis not simply amusing (and some of these memes are highly amusing), but it also produced more evidence that there is an ever-growing audience for LGBT content and that consumers pay attention.

While the needle has certainly moved since Ellen’s television coming out over 20 years ago, major broadcast networks and cable channels are not quite as gay as their streaming parts. The revival of NBC’s Will & Grace, one of the first major network shows to feature gay main characters, has been met with mixed reviews.

Jane the Virgin on the CW and SyFy’s The Magicianshave garnered some discussion about LGBT narratives and relationships. The bulk of queer content, however, is still streaming and through digital platforms. For her work on Master of None, including a much-heralded coming out episode, Lena Waithe became the first black woman to win an Emmy for writing earlier this year. Also on Netflix is Queer Eye, areboot of the formerly-named makeover show Queer Eye for Straight Guy, which has the web abuzz with conversation.The original version of the Fab Five, a group of gay men who help straight men solve their fashion woes, was set in New York City, but the current edition features a “Trump-era Atlanta”, arguably further proof of the mainstreaming of gay culture. Fans and critics alike have lauded the show as “a cure for our masculinity crisis” and as “topical and unpatronizing in its approach to contemporary politics.”

Despite the positive reviews and diversity-affirming stories like those above, naysayers and detractors still exist. That a web search for “Netflix LGBT genre” yields front-page results with users asking how to remove this genre and subsequently tagged films from their view proves that LGBT media is still considered controversial by some, though perhaps a vocal minority.

Furthermore, not everyone sees the mainstreaming of queer content as unconditionally positive. Eve Ng, a media researcher at Ohio University, often discusses what she calls media gaystreaming, the process by which queer narratives are appropriated in mainstream media. Ru Paul’s Drag Race, which recently moved from its original home on LOGO Network to VH1, exemplifies this transition.

Ng explains that the LOGO network was created to house content that would be appealing to LGBT viewers but its sister network VH1 is more indicative of queer-themed content packaged for straight people, particularly heterosexual women. There are also larger questions of more equitable representations of lesbians, and particularly queer women of color, within the larger LGBT media landscape.

Chris Anderson’s The Long Tail has essentially held true as an explanation of what happens in the new media marketplace, as more products become more easily available to a diversified consumer base. As the LGBT-consumer is certainly not a monolith, some queer content does represent a more niche product, while some content tagged as such is finding a much wider appeal, illustrative of Secret 3: Everything from the margin moves to the center.

While issues of identity and representation will continue to be focal points for content creators and media consumers, there is undeniably more queer content to question, which is certainly the first step toward social equilibrium.