Editor’s Note: A little over a year ago, I asked Dr. Amber L. Hutchins, Associate Professor of Communication at Kennesaw State University, if she would be willing to write something for my blog about all the changes taking place at Disney with the launch of Disney+. (She’s one of the people I follow for their expertise on all things Disney.) But somehow I missed the e-mail where she sent it, and I just found it last week. Fortunately, Dr. Hutchins’ thoughts on the Disney+ streaming service are as relevant now as they were a year ago, and she is forgiving enough to let me still run it. So thank you, Dr. Hutchins, and my apologies for the delay!

Disney+, The Walt Disney Company’s new streaming video service, brings much of the global media company’s vast library of content to screens everywhere. On its launch date, millions of users were met with error messages as the platform struggled to accommodate demand, but this was treated as a minor inconvenience and perhaps added to the excitement for those who were in full “Launch Day” celebration mode, ready experience new shows like The Mandalorian from the Star Wars universe or binge Disney Channel favorites like Even Stevens or Lizzie McGuire.

The number of shows and films available (and those still to come) is extensive but not comprehensive.

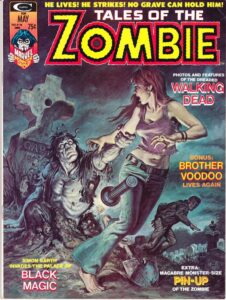

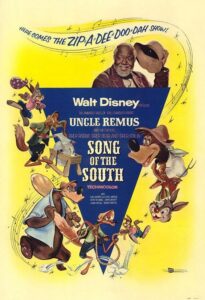

Period poster for Disney’s movie “Song of the South.” Disney has not released the film in any home video format in the United States because of its racist content.

Notably missing is Disney’s Song of the South (1946), which has never been made available via VHS or DVD but remains part of the Disney canon through including of its soundtrack and characters in other Disney properties, including the highly themed theme park attraction Splash Mountain. (Editor’s Note: Since this was written, Disney has committed to remaking the Splash Mountain attraction into a ride featuring Tiana, Disney’s first Black princess, from The Princess and the Frog.) Disney then CEO Robert Iger confirmed that Song of the South won’t appear on Disney+ as it “wouldn’t necessarily sit right or feel right to a number of people today” but some fans and film historians have called for the film’s inclusion in the platform as a way for the company to address the controversy.

In a stroke of impeccable timing, at the same time as Disney+ was launching, the new season of film historian Karina Longworth’s podcast You Must Remember This was dedicated to exploring the history and controversy of Song of the South, and her exhaustive research adds to the discourse about the film’s historical and cultural relevance. Although Disney won’t release the film, bootleg versions are relatively accessible for those who would like to view the film for themselves.

The exclusion of Song of the South is a touchpoint for a broader conversation about Disney’s control over its owned content. Disney+ posts disclaimers about “outdated cultural depictions” before films like the original animated version of Dumbo (1941), as well as missing or altered episodes of former Fox property The Simpsons. In a related issue, theatre owners discovered new restrictions on screening Disney-owned Fox films, limiting access to classics and sending film festivals and independent theatres scrambling. Viewers and industry professionals wonder if titles might disappear permanently (into the mythic Disney Vault, as lampooned by Saturday Night Live—fun fact: I had to watch a Disney+ commercial before I could view this video), and if content will change without notice. (Many Disney classics remain untouched, but some film buffs still recall Ted Turner’s unpopular decision to colorize classic films.)

A Twitter meme poking fun at the Disney+ “Launch Day” technical glitches showed an image of a collection of classic Disney VHS cassettes labeled as “Instantly obsolete” juxtaposed with the Disney+ error screen, suggesting that digital streaming might not be the content utopia we expected, and perhaps we shouldn’t be so hasty to write off physical media.

A modern parable in two acts pic.twitter.com/k1eqiPB69x

— Scott Nye (@railoftomorrow) November 12, 2019

Disney+ is not a historical archive and the company can edit or shelve content as it sees fit, yet we treat Disney media as cultural artifacts or sacred texts to be protected, and we feel entitled to share in ownership.

Disney+ extends the company further into our daily lives, perhaps changing the media industry altogether (again), as some predict. How much say will we have in the new Disney Media Multiverse?