On January 24, 2019, my friend Jeremy Littau, a journalism professor at Lehigh University, started a tweet storm of 30 or so posts that outlined an argument of why news media layoffs keep happening. Within three days, the thread had nearly 7 million impressions. As of this writing it has more than 18,000 retweets and 39,000 likes.

Here’s a lightly edited version of the tweets Jeremy provided to Living in a Media World:

Guest Blog Post by Jeremy Littau

Lehigh University

Dr. Jeremy Littau

For those who aren’t quite sure why these media layoffs keep happening, or think “It’s the internet!” or “People don’t pay to subscribe!” there’s a lot more going on. Those factors are a part of the problem, but their contribution to the distress the news industry is facing is amplified by larger forces.

Here’s a cliffs notes version. It’s not exhaustive, but it hits the highlights.

What is considered The Golden Age of Newspapers ended around the late 1980s. Subscriptions began dropping in the ‘70s year over year, but not enough to show cracks in an industry that was still tremendously profitable.

Newspapers spent most of the 20th century consolidating into chains, but in the latter half of the century they increasingly became part of conglomerates and were publicly traded. Profit margins for companies like Gannett and Knight Ridder were commonly around 30-40%. That’s an insane margin. For comparison, your local supermarket (which arguably is more necessary for you to live) is lucky to clear in the low single digits, often in the 1-2% range.

Anyhow, most of those profits went to shareholders, who came to expect them over time. Because of that, newspapers became, as the joke goes, a license to print money. So chains started gobbling up papers all over the country in the ‘80s and ‘90s. They took on debt to do this because with 40% margins, there wasn’t much downside in that model. During the golden era, newsrooms didn’t invest in innovating their news product very much. They invested in technology to make it easier and require less hands, and soft cuts in the form of job freezes or unfilled open positions were used to serve investors and stock prices; little was invested in the people who made news or the product itself.

This model would have worked fine if newspapers continued unthreatened, but the Internet came along and the bill for shortsighted, quarter-to-quarter thinking came due. They were caught flat-footed, but not immediately because it took some time for the Internet to fully work its way into American households.

I remember as a college student in the ‘90s attending a journalism conference and hearing publishers boast that newspapers were here to stay. They believed their product (not the news, the physical object) was essential. It was a type of hubris that ended up being the problem.

By the mid-‘90s you had chains saddled with MASSIVE debt and already had readership shrinking year over year, things that were a result of the glory days of the previous two decades. Newspapers had a short-term advantage because easy self-publishing on the Internet required technical skill. But along came Blogger in the late 1990s and that was your sea change. Anyone could publish, and publish they did. Blogging software, first with Blogger and then WordPress, led to the proliferation of independent reporters and news efforts across the U.S.

Suddenly, publishers who weren’t used to competition and didn’t invest in innovation were competing with more than their crosstown newspaper rival (if they had one anymore …. consolidations and mergers killed those too). Circulation levels continue to drop, and the trend accelerated in the early part of last decade.

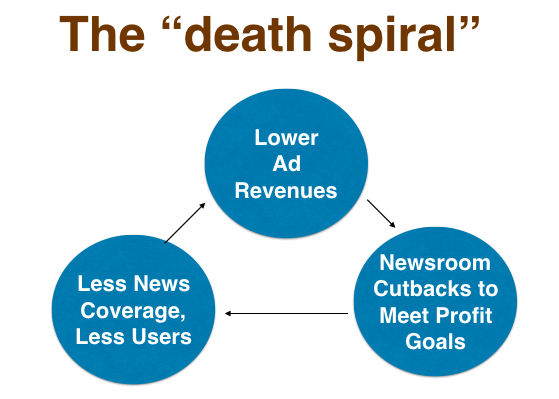

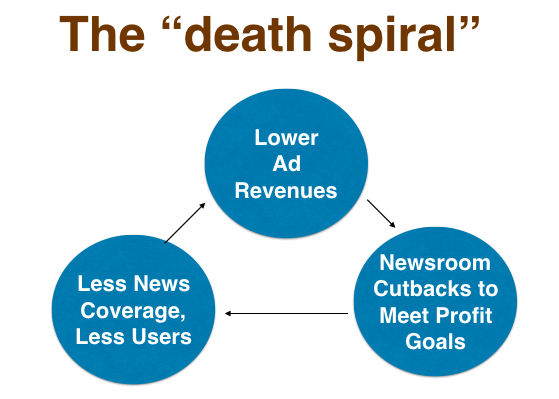

With less readership and huge debt service commitments, it became a vicious spiral that required more cuts to meet debt goals and satisfy shareholders who were used to big profits. And less quality meant fewer people found value in the product, and so they subscribed less. This is what Phil Meyer famously called the Death Spiral.

Newspapers ate their own seed corn during bumper crop days of the ‘80s and then had no resources just when things were getting bad during the last decade, when self-publishing and then mobile were transforming the media industry at incredible speed.

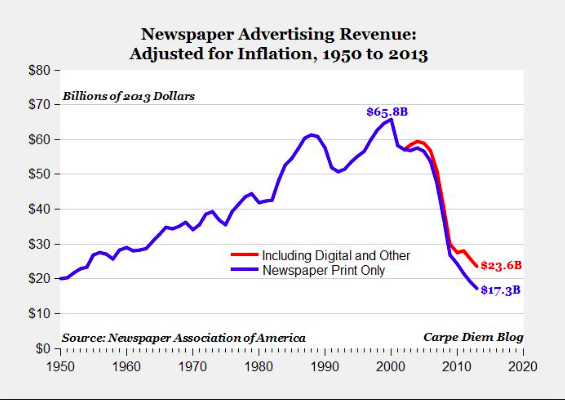

Fewer subscribers didn’t just mean less subscription money. By early 2000 about 75 – 80% of a typical newspaper’s revenue came from display and classified ads. And while subscriptions only account for 10-15% of revenue, a loss of subscribers means less ad revenue. Basically, advertisers will pay a lot if you deliver them a lot of eyeballs, and they’ll pay less if you deliver them less. Losses in subscriptions and rack sales were a double whammy.

And then came free classified ads on Craigislist (among others). People have said Craig Newmark killed newspapers, but that is nonsense. I’m surprised it took people that long to invent free classifieds, to be honest. SOMEBODY was going to do it. At least Newmark cares about news. Classified ads were a damn boondoggle ($500 in a mid-metro to place a car ad, for example). The more expensive your item you needed to market, the more you got charged in classifieds. No wonder people rebelled the minute they were offered the ability to do it for free. Newmark didn’t kill classifieds; news publisher greed did.

Anyhow, by 2006 the storms were gathered. Readership was dropping, which meant less subscription/sale revenue and less display ads, and the classified ads as a business was decimated. And all the while, that debt service from the buying spree years was hanging like the Sword of Damocles.

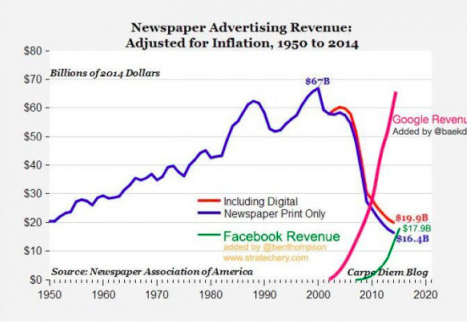

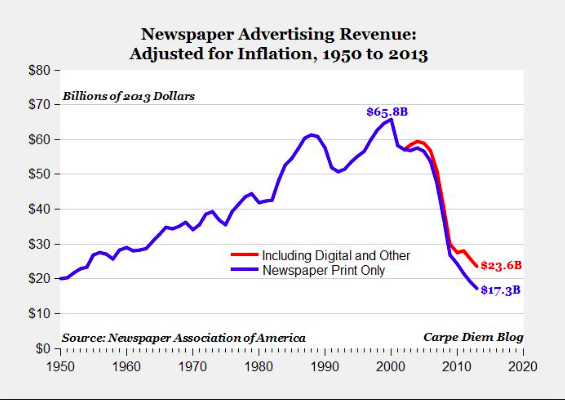

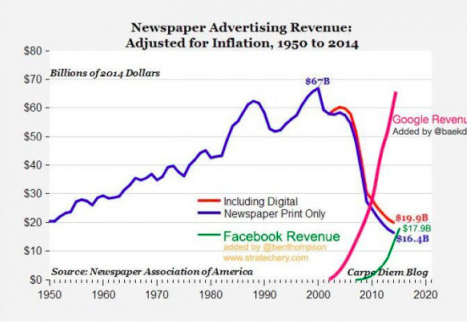

This is a great illustration of it. I call it the Oh My God graphic in my intro course.

So within 10 years, the industry lost about two-thirds of its revenue. And so the Death Spiral accelerated. More cuts, less quality, fewer readers, more cuts, less quality, etc.

But advertisers weren’t spending less. They were redirecting it. The hope was they’d invest in digital, specifically newspaper websites. And while that did happen to some extent, the numbers never came close to matching display ads because how we get news online is way different.

First, social media changed distribution. A print newspaper controlled content and the way you got that content because it controlled distribution. You were basically paying it to point you to the best news. If that sounds familiar, that’s because it’s what Google and Facebook do now.

The value proposition for advertisers is in showing you the way. Consumers value curators. The newspaper was curatorial, it’s just we didn’t realize it because they had a monopoly on the content process from end to end.

So let’s go back to Oh My God, with revisions.

There is money out there. Google and FB have something print newspapers used to have: a reliable, captive audience. That’s what advertisers will pay for, because they know people will be there.

Since the middle part of last decade, newspapers and media companies in general have been accelerated their investment in innovation. There are some GOOD, profitable examples of new companies doing this well. What they have is no debt service millstone tied around their neck.

Some of the big players like the Washington Post and New York Times, they have experimented with innovative products and also paywalls with some success. Long-term their brand and reach are big enough they’ll probably be OK. Yesterday it was Gannett, HuffPo and BuzzFeed announcing layoffs. The latter two were a surprise, but those are digital-first companies that probably have some way through this. The real worry is Gannett.

Here’s what Gannett owns, according to CJR’s excellent Who Owns What database; although it hasn’t been updated since 2011, it is a great way to see how huge these companies are. They own newspapers big and small all over the country. This is the real crisis right here. Most of those small newsrooms have already been cut to the bone repeatedly the past 20 years. We’re way beyond trimming fat. This is a stab to the heart of democratic accountability.

And the crux of this thread is that’s the real worry. I’m less concerned about the national players or a lot of the digital-first operations. We are on the cusp of a country full of news deserts, medium and small communities with no newspaper to watch those in power. And it’s not going to be solved by subscriptions alone, although that can help in big ways. The news model needs to be completely reinvented. Paywalls don’t work for local media, as Brian Moritz has noted.

And who’s moving in right now to pick through the scraps? Hedge funds. They’ve destroyed several papers, and are working their way through some biggies like the Denver Post. When hedge funds are in the game, you’re being stripped for parts to sell off. They have no interest in growing the paper or finding a sustainable model. That’s not what they exist for.

And there’s a demographic bomb out there waiting to go off. The print product is still bringing in large amounts of revenue relative to digital. And guess who reads the print version? Old people (by and large). But this isn’t something that perpetuates. That is, as people like me age up, our likelihood of subscribing to print doesn’t go up. For each successive generation, it’s diminishing returns. So to put it crassly, what happens when that generation of loyal subscribers dies?

And so there’s a limited window before that bomb goes off. But in truth? A healthy product likely would have solved some of this by now. I am resigned to the fear that existing small/medium newspapers are out of time and are simply playing out the string.

So, all that said, what can you do?

First, we need to realize the greedy publishers that didn’t invest aren’t going to realize their mistake and plow money into the business now.

So guess who needs to step up? US. If we value accountable democracy, that is. Subscriptions are a good place to start, yes, but look for opportunities to support things like foundation journalism (what ProPublica is doing, for example) and moonshot ideas like what Civil tried to do (and still might be trying to do; their idea has merit but I’m more skeptical after their token sale failed last fall).

As community members and citizens, we need to look at investments as things that might fail but also might succeed, as investments often do. But we need to invest for the sake of our communities and our democracy.

What I’d implore you to do, though, is look for ways to invest in local news because that is where it matters most. Good god, you think Washington is corrupt? Try City Hall. Some of the worst stuff I saw as a reporter happened there. Local news keeps powerful people accountable, and often it is the only institution advocating for citizen and taxpayer interests.

Your local paper might be toast or dying. So who’s stepping up, needs help creating a new way to do local/regional accountability? Support them.

I’m seeing more of these than I used to. The Nevada Independent is one example. Some of these are laid-off reporters that go-it alone. They’re good at this because they’re not just journalists, but embedded in the communities they serve. I’d point you to a few others. The Texas Tribune for their focus on community. The Correspondent, a startup that is using a membership model to reimagine news coverage and raised more than $2.5 million via over 45,000 people who love journalism and want to help make its future bright. ProPublica, which is doing incredible foundation investigative journalism that is winning Pulitzers. But at the heart of this is community, which is why I always say check out Joy Mayer’s Trusting News project, which offers free training and strategy for journalists to re-engage with readers.

The people in industry, those still there and even those getting laid off, are trying like hell. They really are. But it’s not their fault. It’s not their bias, or mistakes, or them being bad. The seeds were planted decades ago by greedy, short-sighted owners.