Here are several of the Google doodles I discuss in the Ch. 3 Test Your Visual Media Literacy exercise:

The original Burning Man Google doodle

Lotte Reiniger’s 117th Birthday Google doodle

The 44th Anniversary of the Birth of Hip Hop

Here are several of the Google doodles I discuss in the Ch. 3 Test Your Visual Media Literacy exercise:

The original Burning Man Google doodle

Lotte Reiniger’s 117th Birthday Google doodle

The 44th Anniversary of the Birth of Hip Hop

A couple of months ago I saw the following Tweet from my online friend Candice Roberts:

Given that Dr. Roberts knows much more on this subject than I do, I invited her to do a guest blog post, which she so kindly sent!

Dr. Candice Roberts is a media studies researcher and Assistant Professor of Communication who is interested in popular and consumer culture, narratives of identity, and queer theory. Feel free to @ her (@popmediaprof on Twitter).

An April 2018 headline from Autostraddle, an arts and culture website run by and featuring content for lesbian and queer women, highlights “53 Queer TV Shows to Stream on Netflix.” A few years ago 53 different queer-themed television shows on any single, media platform would have seemed implausible if not impossible. Now this list not only exists but is populated with widely recognizable hits such Orange is the New Black and Glee as well as lesser-known shows like The Shannara Chronicles and CW’s Legends of Tomorrow; it also includes several of Netflix’s own original programs like Everything Sucks!, One Day at a Time, Gypsy, and Sense8— the latter of which spurred a major fan campaign when it was cancelled after two seasons. (Netflix ultimately recognized fan dismay and promised Sense8 viewers a two-hour series finale as a consolation.)

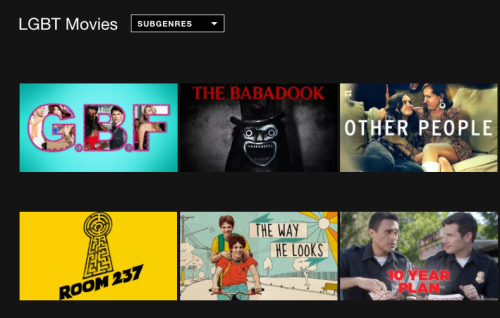

Netflix and streaming-competitor Hulu introduced LGBT sections and genre tags in 2012. Despite Hulu’s blog post concerning the category launch, the rollouts on both sites happened relatively quietly, with consumers discovering the new additions on their own and most of the publicity coming via word of mouth.

An algorithmic snafu in 2016, however, drew more attention to Netflix’s LGBT movies genre. When Tumblr user Taco-bell-ray posted a screenshot of his Netflix interface showing horror film The Babadook represented within the LGBT Movies category, the Internet did what it does best: meme’d this mistake for all it’s worth.

By the summer of 2017, the Gay Babadook had spread. While Netflix did not comment directly on the incident, the official Twitter account hinted at the company’s social media savvy and corporate awareness. The erroneous sorting of The Babadookis not simply amusing (and some of these memes are highly amusing), but it also produced more evidence that there is an ever-growing audience for LGBT content and that consumers pay attention.

While the needle has certainly moved since Ellen’s television coming out over 20 years ago, major broadcast networks and cable channels are not quite as gay as their streaming parts. The revival of NBC’s Will & Grace, one of the first major network shows to feature gay main characters, has been met with mixed reviews.

Jane the Virgin on the CW and SyFy’s The Magicianshave garnered some discussion about LGBT narratives and relationships. The bulk of queer content, however, is still streaming and through digital platforms. For her work on Master of None, including a much-heralded coming out episode, Lena Waithe became the first black woman to win an Emmy for writing earlier this year. Also on Netflix is Queer Eye, areboot of the formerly-named makeover show Queer Eye for Straight Guy, which has the web abuzz with conversation.The original version of the Fab Five, a group of gay men who help straight men solve their fashion woes, was set in New York City, but the current edition features a “Trump-era Atlanta”, arguably further proof of the mainstreaming of gay culture. Fans and critics alike have lauded the show as “a cure for our masculinity crisis” and as “topical and unpatronizing in its approach to contemporary politics.”

Despite the positive reviews and diversity-affirming stories like those above, naysayers and detractors still exist. That a web search for “Netflix LGBT genre” yields front-page results with users asking how to remove this genre and subsequently tagged films from their view proves that LGBT media is still considered controversial by some, though perhaps a vocal minority.

Furthermore, not everyone sees the mainstreaming of queer content as unconditionally positive. Eve Ng, a media researcher at Ohio University, often discusses what she calls media gaystreaming, the process by which queer narratives are appropriated in mainstream media. Ru Paul’s Drag Race, which recently moved from its original home on LOGO Network to VH1, exemplifies this transition.

Ng explains that the LOGO network was created to house content that would be appealing to LGBT viewers but its sister network VH1 is more indicative of queer-themed content packaged for straight people, particularly heterosexual women. There are also larger questions of more equitable representations of lesbians, and particularly queer women of color, within the larger LGBT media landscape.

Chris Anderson’s The Long Tail has essentially held true as an explanation of what happens in the new media marketplace, as more products become more easily available to a diversified consumer base. As the LGBT-consumer is certainly not a monolith, some queer content does represent a more niche product, while some content tagged as such is finding a much wider appeal, illustrative of Secret 3: Everything from the margin moves to the center.

While issues of identity and representation will continue to be focal points for content creators and media consumers, there is undeniably more queer content to question, which is certainly the first step toward social equilibrium.

Aaron Blackman

The following is a guest blog post by my colleague Aaron Blackman, who in addition to being a forensics coach and comm lecturer is also a big fan of video and tabletop games. He also streams video games and writes about video games and e-sports.

Four months into 2018 and the world of streaming video games is rapidly evolving.

In February, a Twitch record for concurrent viewers (along with actual downtime of the entire website) after the popular streamer “DrDisRespect” returned from a two month absence. An over-the-top character played by Guy Beahm, DrDisRespect claimed himself to be the “Face of Twitch” due to high viewer counts, dedicated fanbase, and extremely polished production quality. Reaching 389,000 concurrent viewers while streaming PlayerUnknown’s Battlegrounds was a feat only accomplished by Esports tournaments or press conferences for E3. Having a single streamer attain popularity of this kind was groundbreaking for the world of Twitch.

However, as 2018 progressed, the popularity of battle royale games reached a fever pitch and PlayerUnknown’s Battlegrounds (PUBG) was replaced with Fortnite, a free-to-play game found on PC, Playstation 4 and Xbox One. If you are wondering what a battle royale game is, think Hunger Games where 100 players enter an arena in a fight to the death, but there can only be one player (or team of players) standing. Fortnite shares many of the same elements of PUBG, but the free price tag, smaller map, console availability and building mechanics set it apart.

In March, the most popular Fortnite streamer was Tyler Blevins, also known as “Ninja”. A former pro gamer, Ninja had been streaming since 2011 when his channel rapidly rose to the top of Twitch charts alongside an Amazon Prime promotion for in-game Fortnite items. His stellar play was noticed by Canadian rapper and fellow gamer Drake, and the two began to communicate to play Fortnite one night.

Twitch Clip: Ninja’s wife meets Drake:

On March 14, Ninja began streaming Fortnite with a special guest: Drake. Without fanfare or any lead-up promotion, the two met online and started playing the game, while the viewers promoted it all over Twitter. The stream shattered the previous concurrent viewer record by reaching 628,000 viewers, and eventually rapper Travis Scott alongside Pittsburgh Steelers Wide Receiver JuJu Smith-Schuster joined in on the fun. Ninja gained scores of followers and subscribers on Twitch in a monumental night that shifted the bar for a successful Twitch stream.

This is fantastic for gaming and streaming for everyone.

It’s all about exposure.

— Dr Disrespect (@DrDisrespect) March 15, 2018

As of writing this post on Thursday April 26, 2018, Ninja had 202,272 Twitch subscribers. These $5 monthly subscriptions split the money between the streamer and Twitch itself. At the entry end of the spectrum, I make $2.50 off of each subscription as a Twitch Affiliate. Popular streamers like Ninja are considered a Twitch Partner and get a better deal. So with 200,000 subscribers, Ninja is making over $500,000 a month from subscriptions alone for playing games in front of fans. This doesn’t factor in the scores of donations and higher-tiered subscriptions that roll in from viewers as well. He’s earning all of this money from the comfort of his own home.

While writing this blog post, Ninja was live and streaming Fortnite, his bread and butter game. He was playing host to over 100,000 viewers, an average amount for his streams, which is staggering considering it was a Thursday afternoon. Compare this DrDisRespect’s 22,000 viewers observing his “speed, violence and momentum” in PlayerUnknown’s Battlegrounds at the same time.

On Saturday April 21, Ninja hosted his own style of live event in the form of a Fortnite competition hosted at the new Esports Arena in Las Vegas. Fans were able to pay $75 to enter, giving them a spot in two of the night’s ten games. Ninja played each game and gave $2,500 to the last player standing in each game, as well as a $2,500 bounty for the player who killed Ninja in Fortnite.

Clearly Ninja struck a chord with viewers as his Las Vegas event broke his own Twitch viewership record by attracting 667,000 viewers at its peak. It also offered fun and compelling storylines like a 14-year old who took home $2,500 by winning one of the night’s games.

One fascinating thought was brought up by Brian Mazique in his Forbes article prior to the event, likening streamers to singers playing the Vegas circuit. Could this be the next step for popular streamers? Ninja fits a unique mold with his rapid rise on Twitch and Fortnite’s popularity skyrocketing to an all-time high. Additionally, Fortnite has no organized Esport competitions as of yet, so it made sense for its most popular streamer to host his own style of live tournament.

Streamers wanting to host their own events would need a large and active fanbase to ensure an event of this magnitude wasn’t a dud. For now, Ninja’s success is an anomaly in the streaming world. Combining universality in his appeal and creating fun connections with celebrities turned fans has elevated him to a new level.

2018 is a new era for streaming video games, and we are just getting started.

I asked my commentary and blogging students to do a post this week on their reactions to the Pulitzer Prizes announced this week. Here’s what they had to say:

The announcement of this year's Pulitzer Prizes reminds me: Subscribe to a newspaper. Journalists do important work holding power accountable & seeking the truth from those who want to hide it. Well-reported news isn't free.

— John Robinson (@johnrobinson) April 16, 2018

I always look forward to when the Pulitzer Prizes get announced. Not just for the predictable ones (well deserved!) that go to news outlets like the New York Times, The New Yorker and The Washington Post for reporting on issues of global import, but also those that go to local and regional papers for coverage that would otherwise not get the attention they richly deserve. Here’s a summary of who won the major prizes (i.e., the one’s I care about) this year:

Jake Halpern & Michael Sloan – For Editorial Cartooning

To call “Welcome to the New World” and editorial cartoon is vastly underselling the tremendous accomplishment by writer Halpern and cartoonist Sloan. This is nothing less than a graphic novel treatment of the story of a real-life refugee family from Syria who left for the United States on 2016 election day. What? No! I wasn’t grabbing a handkerchief… Really. All kidding aside. This is visual storytelling at it’s best. And while other stories will be more consequential overall, this is the one that really hit me.

And here’s an interview with writer Jake Halpern talking about how he got involved with the project from Buffalo Spree magazine.

The Roy Moore Senate Race Story from Alabama

There were two separate prizes given to two very different news organizations on the Roy Moore sex abuse senate race story.

Not surprisingly, the Washington Post got the Pulitzer for Investigative Reporting tor their “purposeful and relentless reporting that changed the course of a Senate race in Alabama by revealing a candidate’s alleged past sexual harassment of teenage girls and subsequent efforts to undermine the journalism that exposed it.”

Part of what made the Post’s reporting so compelling was not just the true things they reported, but the false reports they uncovered. The following video tells the story of an attempt to get the Post to report on a made-up story about Moore paying for an abortion.

The second Pulitzer for the Roy Moore story went to John Archibald of the Alabama Media Group out of Birmingham, Alabama for his commentary on a state that he clearly loves and is still able to be critical of. The Moore story was just one of the one’s he wrote about so beautifully. In a column published the day after Alabama elected Democrat Doug Jones to the U.S. Senate instead of Roy Moore, Archibald says:

But Alabama, against the odds and conventional wisdom, stood and rejected that behavior.

It did not condone the silence. It did not excuse the sin.

It made a political decision that many found hard, a decision that put decency over party, character over tribe. It stood for its mothers and sisters and daughter and fellow human beings.

When nobody thought it would.

That’s the message Alabama sent yesterday. Not just about politics, or fear, or loathing, or habit, or even Donald Trump.

It sent a message to women: This has not been a safe place. But it can be. It can.

And finally, I would note Andie Dominick of the Des Moines Register winning for her editorials on Iowa’s privatizing of the state’s administration of Medicaid, and what that means for health care for Iowa’s poorest citizens. There is an old platitude that says it is the job of journalists to comfort the afflicted and afflict the comfortable. And that’s clearly what’s going on here. (I would also note that this is two years in a row that the Pulitzer for editorial writing has gone to an Iowa newspaper. Last year it went to Art Cullen, editor of the Storm Lake Times.)

I might also note that two of the stories I’ve singled out for discussion here deal with diabetes one form or another. Ms. Dominick has also written a memoir about living with diabetes, and the mother in “Welcome to the New World” is dealing with living as a refugee with diabetes.

Here’s a link to all the rest of this year’s winners. There’s lots here I didn’t talk about. Look and read (or listen).

This week I asked my commentary and blogging students to write a blog post on media criticism. Here’s what each of them came up with:

And while you are looking at these blog posts, why not check out Humans of Kearney?

With everything else going on, you may be forgiven for missing reports that President Trump is considering issuing a pardon to Lewis “Scooter” Libby, who was at one time Vice President Dick Cheney’s chief of staff. If you need a refresher, here’s what the Washington Post has to say:

Libby was convicted of making false statements, perjury and obstruction of justice in the 2007 investigation of [Valerie] Plame, a former covert CIA agent and the wife of former ambassador Joseph C. Wilson IV.

Libby was sentenced to 30 months in prison and fined $250,000, but his sentence was commuted by Bush. Although spared jail time, Libby was not pardoned.

Scooter Libby’s possible pardon brings back to mind one of my favorite blog posts ever: a New York Metropolitan Opera Broadcast-style opera plot summary for an imagined political musical theatre piece – Plamegate – The Opera.

I have no idea how many of these links still work 13 years later, but I thought it was fun:

Nov. 18, 2005

You may recall that in my Oct. 12th entry I wrote:

You may recall that in my Oct. 12th entry I wrote:

Any of you who thinks Miller testifying before the grand jury was the closing act of this political opera is confused. It is at best at the close of the second act (of a three or four act show

I’ve now got a firmer handle on how this opera should be staged.

The first act has two great arias in it, “There’s yellowcake in Niger” sung by The President, and “Ambassadors and Agents” sung by Robert Novak.

The second act features arias, ensembles, and a lot of recitative. Patrick Fitzgerald kicks things off with “Tell me a story,” followed by the trio with Judith Miller and Matt Cooper “I’ve got a subpoena.” Cooper then has his show stopping duet with Time editor Norman Pearlstine, “We’ve run out of options” followed by his aria “I have been released.” The act ends with the giant choral number “Judy’s turn to cry…” as Miller heads off to jail.

Act three picks up two-and-a-half months later with Miller’s testimony before the grand jury. She starts with a reprise of “I have been released,” followed by Scooter Libby’s “Dear Judy, the aspens are turning.” Following an extended recitative from Miller “I really don’t recall,” comes the major ensemble piece of the act, the incredibly snarky “We’ve never really liked her” sung by a large cast of reporters and bloggers. Prosecutor Fitzgerald then has his major aria of the show, “Scooter Libby, I Accuse You.” Audience members will no doubt break out in great applause at the end of his powerful number, thinking that the third act is coming to a close. But then the bloggers break out with a quick tempoed “It’s Fitzmastime” as a transition to the surprise true end to the act – Bob Woodward’s dramatic, “I’m sorry, I knew it all along.”

The question now is how to end this opera. Will it turn out in the end to be a tragedy or a farce? It certainly can’t be comedic at this point.

Think this is all too far fetched? Try taking a listen to my favorite contemporary opera, John Adams’ incomparable Nixon in China.

UPDATE: The Rambling Freshman has put together a cool poster for Plamegate. Thanks, Dave.

This week I’m at the Western Social Science Association annual conference. I’m giving a presentation on the explosion of stories in the news media about sexual harassment by high profile men, especially those in the media industry. Rather than writing a conventional conference paper, I will have series of blog posts covering my topic over the next day or so.

Resetting the Agenda:

How Sexual Harassment & Assault

Became The Story of 2017 – Part 3

So where did it really start?

So if this story of sexual harassment didn’t start with Harvey Weinstein, when did it? The media’s interest and concern about sexual misconduct by men could also date back two years when news first started breaking about Bill O’Reilly paying out multiple private settlements and being forced out at Fox News for his behavior.

Or it could be 27 years ago when Anita Hill testified about Clarence Thomas’s behavior toward her at his Supreme Court confirmation hearings. But while Ms. Hill brought a lot of attention toward the issue during those hearings, her testimony didn’t stop Thomas’s confirmation.

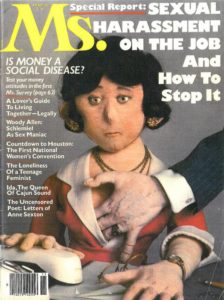

The cover story of the November 1977 issue of Ms. magazine was about sexual harassment (New York Times

But perhaps one of the best dates to choose would be just over 40 years when, according to the New York Times, Ms. magazine published their first cover story on sexual harassment in 1977. As journalist Jessica Bennett points out, “Understanding the sensitivity of the topic, the editors used puppets for the cover image — a male hand reaching into a woman’s blouse — rather than a photograph. It was banned from some supermarkets nonetheless.” She goes on to note that sexual harassment was not yet a legal concept and was just entering into our vocabulary.

Despite being more than 40 years old now, the story is still disturbingly fresh:

“It describes an executive assistant who quit after her boss asked for oral sex; a student who dropped out after being assaulted by her adviser; a black medical administrator whose white supervisor asked if the women in her neighborhood were prostitutes — and, subsequently, if she would have group sex with him and several colleagues.

“Citing a survey in which 88 percent of women said they were harassed at work, the author said the problem permeated almost every profession, but was particularly pernicious ‘in the supposedly glamorous profession of acting,’ in which Hollywood’s casting couch remained a ‘strong convention.’”

The Story After Harvey

It would be impossible in anything under a New Yorker long read to try to talk exhaustively about all the men who have been accused and fired since Harvey Weinstein was forced out of the company that bears his name.

There doesn’t seem to be any limits to where these stories emerged from. While there had clearly been a culture at Fox News that tolerated bad behavior from evening talk show host Bill O’Reilly and from network founder Roger Ailes, there were also journalists, executives and performers from CNN, NPR, PBS, the New York Times, the left-leaning online news source Vox, streaming giant Netflix, and NBC’s news, entertainment and reality programming.

There are certain commonalities that emerge from these stories:

Someone wants to cover for the offenders

NPR chief executive Jarl Mohn went on medical leave from the non-commercial radio company in November of 2017, claiming blood pressure problems. But he also may have taken leave for how he handled charges against editor Mike Oreskes.

There are accussations that when two sets of charges came forward independently about Oreskes, Mohn worked to bury them. Mohn used a variety of arguments for why he did not discuss all the charges against Oreskes. Among these were:

People make excuses for the abuser and the abuser makes a mild apology.

Television host Charlie Rose, who had a long-running interview program on PBS as well as reporting for CBS and Bloomberg TV faces charges from at least eight women that he “made unwanted sexual advances toward them, including lewd phone calls, walking around naked in their presence, or groping their breasts, buttocks or genital areas.”

Rose’s comments seemed typical from the flood of stories:

“In my 45 years in journalism, I have prided myself on being an advocate for the careers of the women with whom I have worked. Nevertheless, in the past few days, claims have been made about my behavior toward some former female colleagues.

“It is essential that these women know I hear them and that I deeply apologize for my inappropriate behavior. I am greatly embarrassed. I have behaved insensitively at times, and I accept responsibility for that, though I do not believe that all of these allegations are accurate. I always felt that I was pursuing shared feelings, even though I now realize I was mistaken.

“I have learned a great deal as a result of these events, and I hope others will too. All of us, including med, are coming to a newer and deeper recognition of the pain caused by conduct in the past, and have come to a profound new respect for women and their lives.”

Here is where we see the next step of the story. PBS and Bloomberg TV stopped distributing Rose’s show and CBS suspended him.

Another common element – stories about these men had been surfacing for years but they hadn’t gotten attention.

When assistant Kyle Godfrey-Ryan complained to Rose’s long-time executive producer, she said her response was “That’s just Charlie being Charlie.”

Accusers didn’t want to talk about it

A Washington Post contributor said she had tried to report on a pair of cases involving Rose for the blog Jezebel in 2010, but she was unable to get confirmation. She started digging back into it aggressively when the Harvey Weinstein story started breaking.

Rose had been divorced since 1980, and the late Radar magazine called Rose a “toxic bachelor” in 2007 and reported charges of him groping an unnamed woman. Rose’s attorney at the time demanded a retraction from Radar but the publication refused.

This was also a story where there was a serious disparity in power. These young women would tolerate abuse because they wanted jobs. The women also say they didn’t want to admit to themselves how they were being treated so they pretended it hadn’t happened.

One of the women told the Post, “Remaining silent allowed me to continue denying what had occurred. It was a state of denial that I wrote to him asking about the job.”

Conclusion: A Story Framed by Critical Theory

When I wrote the abstract to propose this paper several months ago, I assumed I was writing a paper about agenda setting, as I discussed at the beginning of the paper. But I no longer think that’s the central issue here. (I’m sure there is some level of agenda setting going on, but it would take more evidence than I have here to document it.)

I would suggest instead, that this is a story of women finally speaking up and forcing the media to listen to them; to put their (justifiable) fears behind them; to hold their abusers accountable.

As I wrote at the beginning:

Critical theory can be summarized with the following principles:

A commentary written in December 2017 by Manhole Dargis, the co-chief film critic for the New York Times, argues that the physical abuse of women started to get talked about more when the financial and status abuse of women in the film industry broke in 2014 when the computers at Sony were hacked and large numbers of documents with business notes were disgorged.

The files showed how much more men got paid than women in movies, and how women were often not even considered as candidates to direct major films.

Dargis discusses the institutional sexism that has long been in the movie industry by quoting from Molly Haskell’s seminal 1974 book on sexism in Hollywood, From Reverance to Rape: The Treatment of Women in the Movies. Haskell writes:

“Through the myths of subjection and sacrifice that were its fictional currency and the machinations of its moguls in the front offices, the film industry maneuvered to keep women in their place; and yet these very myths and this machinery catapulted women into spheres of power beyond the wildest dreams of most of their sex.”

And it’s this combination that we see coming through all of the comments from women in Hollywood today.

Dargis says that for herself she battles with how much attention she has to give to the issues of sexism in the movies when she confronts just wanting to enjoy a great movie:

“It can be exhausting. Sometimes, you just want to watch a movie, not keep a running inventory of each affront, every offensive line or beat. Did women direct, write, produce, star? Does the female lead have anything of interest to say? Why is she taking off her underwear for the lovemaking scene while the guy keeps his on? Why is her breast showing? Why is she smiling (always smiling)? Why is she a hooker? Or dead? Is she merely there, kind of like the dog or a pricey lamp, so she can suggest that the hero is also an Everyman?”

Sexual Harassment & Assault:

This week I’m at the Western Social Science Association annual conference. I’m giving a presentation on the explosion of stories in the news media about sexual harassment by high profile men, especially those in the media industry. Rather than writing a conventional conference paper, I will have series of blog posts covering my topic over the next day or so.

Resetting the Agenda:

How Sexual Harassment & Assault

Became The Story of 2017 – Part 2

How the story broke – Ashley Judd:

Mandatory Credit: Photo by Jim Smeal/BEI/REX Shutterstock (2211284i)

Ashley Judd

‘Olympus Has Fallen’ film premiere, Los Angeles, America – 18 Mar 2013

While the story of women being sexually harassed and abused by powerful men had been slowly breaking further and further into the media for several years, the real explosion came when actress Ashley Judd went public with her story from two decades earlier.

Judd told the New York Times in early October, 2017 that she went what she thought was going to be a breakfast meeting at a hotel. She was instead sent up to Weinstein’s room where he greeted her wearing a bathrobe and suggested either he give her a massage or she could “watch him shower.”

It is at this point that we see the basic elements of the narrative coming through. Judd had to figure out how to get out of the room without alienating one of the most powerful producers in Hollywood.

The Times goes on to report that Weinstein reached “at least eight settlements with women,” paying them to drop their claims and keep their silence. When all of these stories started surfacing, Weinstein said in a statement to the Times:

“I appreciate the way I’ve behaved with colleagues in the past has caused a lot of pain, and I sincerely apologize for it. Though I’m trying to do better, I know I have a long way to go.”

He also said, through his lawyer, that “he denies many of the accusations as patently false.”

So again, why did these stories start breaking now? Judd said,“Women have been talking about Harvey among ourselves for a long time, and it’s simply beyond time to have the conversation publicly.”

Judd had previously talked about what had happened with Weinstein back in 2015 with Variety magazine, but she didn’t name him.

Judd told Variety she felt bad because she didn’t do antying about it at the time:

“I beat myself up for a while. This is another part of the process. We internalize the shame. It really belongs to the person who is the aggressor. And so later, when I was able to see what happened, I thought: Oh god, that’s wrong. That’s sexual harassment. That’s illegal. I was really hard on myself because I didn’t get out of it by saying, ‘OK motherf—er, I’m calling the police.’”

The common theme between Judd and the other women who say Weinstein abused or harassed them was that women didn’t speak out because they didn’t know each other, didn’t live in the same cities. But while they didn’t talk about it publicly, they did talk about it among themselves.

So what kept the stories silent?

Sexual Harassment & Assault:

This week I’m at the Western Social Science Association annual conference. I’m giving a presentation on the explosion of stories in the news media about sexual harassment by high profile men, especially those in the media industry. Rather than writing a conventional conference paper, I will have series of blog posts covering my topic over the next day or so.

Resetting the Agenda:

How Sexual Harassment & Assault

Became The Story of 2017

ABSTRACT: In the fall of 2017, it seemed as though there was a new story of a powerful man in media or politics being outed for sexual misconduct on almost a daily basis. The story became a powerful narrative leading to Time magazine declaring the Person of the Year for 2017 to be “The Silence Breakers” – the women (and men) who have spoken out about suffering sexual abuse. This paper looks at how sexual harassment and abuse became the dominant story of late 2017, and how media organizations dealt with a narrative that cut directly into their business.

Introduction:

In my intro to mass comm textbook, Mass Communication: Living in a Media World, I have a series of principles of media literacy. They cover a range of topics that range from the incredibly obvious – “Media are a central component of our lives.” – to the somewhat more subtle – “Nothing’s new: Everything that happens in the past will happen again.”

But by far the most significant of these Seven Secrets They Don’t Want You To Know About the Media (which I think sounds infinitely more interesting than Seven Principles of Media Literacy) is Number 3 – “Everything from the margin moves to the center.”

When I introduce this principle, I note:

“One of the mass media’s biggest effects on everyday life is to take culture from the margins of society and make it into part of the mainstream, or center. This process can move people, ideas, and even individual words from small communities into mass society.”

Over the last year, attention to the issue of sexual harassment and abuse has become the major cultural stories for our media, both sensational and serious, have moved this issue from the margins of society to the center. While there could be many points on the timeline we could highlight as the start of the media’s focus on sexual harassment and abuse, it is often connected to when multitudes of women started coming forward and telling their stories of mistreatment at the hands of Hollywood producer Harvey Weinstein.

In fact, the New York Times started keeping track of the number of men who have been fired or forced to resign over accusations of sexual misconduct since Weinstein was fired from the company that bears his name in early October.

As of Feb. 8, 2018, the Times count had reached 71. The Times had a second list of 28 men who had faced charges of sexual misconduct but who had only been suspended or similar lesser punishment. The list was a Who’s Who of the powerful behind and in front of the scenes in the entertainment business, industry, and politics.

In addition to producers, these men included writers, actors, editors, comedians, senators, congressmen, dancers, radio hosts, journalists, photographers, bloggers, and just about every other media or government job description you could come up with.

So if Oct. 8, 2017 is the start of the explosion of this story with the firing of Weinstein, it certainly wasn’t the start of the story. According to the Times, the accusations and rumors about Weinstein date back for three decades. It wasn’t as though these stories weren’t known about by reporters, they simply weren’t reported.

So this leaves us with the question:

Why, after years of neglect, did the press in all its varied forms, suddenly start paying attention to these accusations, and the women making them?

While this paper is not an in-depth data analysis of how the story spread, I think we could consider answering this question using a couple of different theoretical approaches:

Sexual Harassment & Assault: