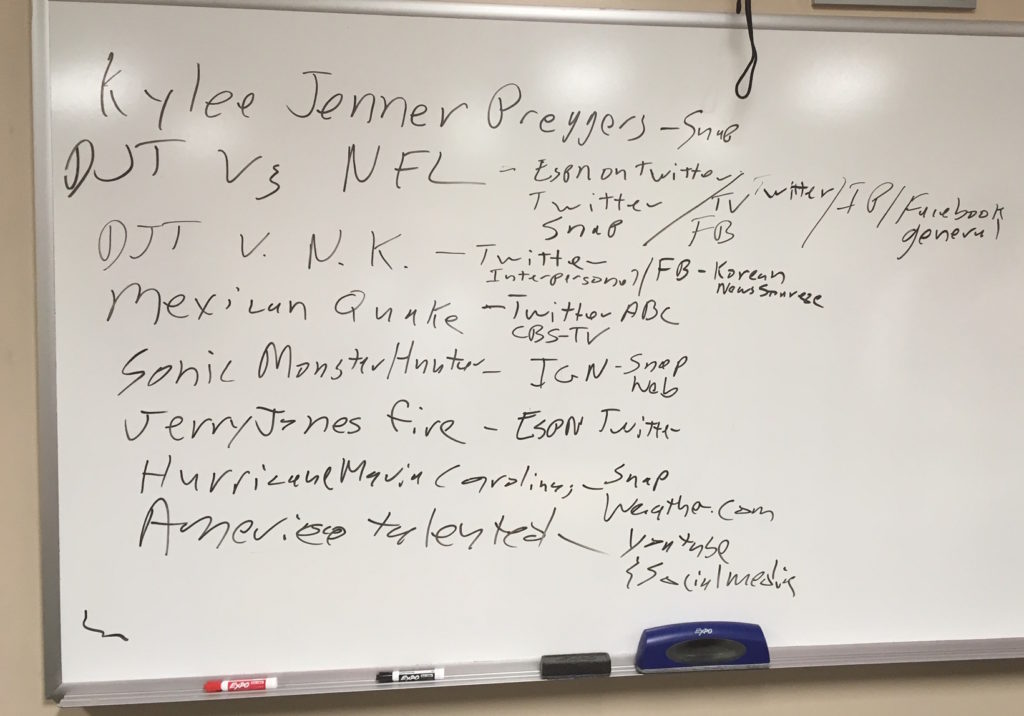

Over the last couple of days, Martin Luther King, Jr.’s “Letter from a Birmingham Jail” has been getting lots of mention on Twitter and other social media in reaction to the NFL players and management participating in the #takeaknee protests.

Here’s a typical example with a tweet from Nebraska Senator Ben Sasse followed by one from religion writer Rachel Held Evans:

If you do a search on Twitter for “Birmingham Jail,” you will literally come up with hundreds of references to it over the last month. With all that attention, I think it is worth reposting a talk I gave at the Martin Luther King, Jr. candlelight vigil in 2015. Here’s what I had to say:

When we think of public relations, we think of a professional in a suit trying to persuade us about something related to a large corporation. But not all PR is practiced by big business.

When we think of public relations, we think of a professional in a suit trying to persuade us about something related to a large corporation. But not all PR is practiced by big business.

Civil rights leader The Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. had a brilliant understanding of public relations during the campaign to desegregate Birmingham, Alabama in 1963.

The goal of the campaign was to have non-violent demonstrations and resistance to force segregated businesses to open up to African Americans. What King, and the members of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, wanted to do was stage a highly visible demonstration that would not only force change in Birmingham, but also grab the attention of the entire American public.

King and his colleagues picked Birmingham because it was one of he most segregated cities in America and because it had Eugene “Bull” Conner as police commissioner.

Conner was a racist who could be counted on to attack the peaceful marchers. Birmingham was a city where black protestors were thrown in jail, and the racists were bombing homes and churches. There was a black neighborhood that had so many bombings it came to be known as Dynamite Hill.

Dr. King and his colleagues had planned demonstrations and boycotts in Birmingham, but held off with them in order to let the political system and negotiations work. But time passed, and nothing changed. Signs were still up at the lunch counters and water fountains, and protestors were still headed to jail.

King and the rest of the SCLC needed to get attention for the plight of African Americans in cities like Birmingham.

They needed to do more than fight back against the racism of segregation. They needed to get Americans of good will in all the churches and synagogues to hear their voices.

Starting in April of 1963, predominantly African American volunteers would march in the streets, hold sit-ins at segregated lunch counters, and boycott local businesses in Birmingham. As the protests started, so did the arrests.

On Good Friday, King and Abernathy joined in the marching so that they would be arrested. While King was in jail, he was given a copy of the Birmingham News, in which there was an article where white Alabama clergy urged the SCLC to stop the demonstrations and boycotts and allow the courts to solve the problem of segregation.

But King was tired of waiting, and so he wrote what would become one of the great statements of the civil rights cause. One that spoke to people who were fundamentally their friends, not their enemies. This came to be known as the “Letter from a Birmingham Jail.”

Writing the letter was not easy. Dr. King wrote it in the margins of the newspaper. He wrote it on scraps of note paper. He wrote it on panels of toilet paper. (Think about what the toilet paper was like if Dr. King was able to write on it!)

The letter spoke to the moderates who were urging restraint. To them, he wrote:

“My Dear Fellow Clergymen:

While confined here in the Birmingham city jail, I came across your recent statement calling my present activities “unwise and untimely.” Seldom do I pause to answer criticism of my work and ideas…. But since I feel that you are men of genuine good will and that your criticisms are sincerely set forth, I want to try to answer your statement in what I hope will be patient and reasonable terms.”

He went on the acknowledge that perhaps he was an extremist, but that he was an extremist for love, not for hate:

“But though I was initially disappointed at being categorized as an extremist, as I continued to think about the matter I gradually gained a measure of satisfaction from the label.

Was not Jesus an extremist for love: “Love your enemies, bless them that curse you, do good to them that hate you, and pray for them which despitefully use you, and persecute you.”

Was not Amos an extremist for justice: “Let justice roll down like waters and righteousness like an ever flowing stream.” …

Was not Martin Luther an extremist: “Here I stand; I cannot do otherwise, so help me God.” …

And Abraham Lincoln: “This nation cannot survive half slave and half free.”

And Thomas Jefferson: “We hold these truths to be self evident, that all men are created equal . . .”

So the question is not whether we will be extremists, but what kind of extremists we will be. Will we be extremists for hate or for love?”

King’s jailhouse writings were smuggled out of the jail and published as a brochure. His eloquent words were given added force for being written in jail. As he says toward the end of his letter, it is very different to send a message from jail than from a hotel room:

“Never before have I written so long a letter. I’m afraid it is much too long to take your precious time. I can assure you that it would have been much shorter if I had been writing from a comfortable desk, but what else can one do when he is alone in a narrow jail cell, other than write long letters, think long thoughts and pray long prayers?”

Once King was released from jail eight days later, he and his followers raised the stakes. No longer would adults be marching and being arrested, children would become the vanguard. And as the children marched, photographers and reporters from around the world would document these young people being attacked by dogs, battered by water from fire hoses, and filling up the Birmingham jails.

King faced criticism for allowing the young people to face the dangers of marching in Birmingham. But he responded by criticizing the white press,  asking the reporters where they had been “during the centuries when our segregated social system had been misusing and abusing Negro children.”

asking the reporters where they had been “during the centuries when our segregated social system had been misusing and abusing Negro children.”

Although there was rioting in Birmingham, and King’s brother’s house was bombed, the campaign was ultimately successful. Business owners took down the signs that said “WHITE” and “COLORED” from the drinking fountains and bathrooms, and anyone was allowed to eat at the lunch counters. The successful protest in Birmingham set the stage for the March on Washington that would take place in August of 1963, where King would give his famous “I have a dream” speech.[King, 1998 #552],[Kasher, 1996 #553]

for the March on Washington that would take place in August of 1963, where King would give his famous “I have a dream” speech.[King, 1998 #552],[Kasher, 1996 #553]

We are now more than fifty years from King’s letter from Birmingham Jail. This letter was not one of his “feel good” speeches. It doesn’t raise the spirit the way his I have a dream speech did.

But it did give us a message that still matters today:

“I hope this letter finds you strong in the faith. I also hope that circumstances will soon make it possible for me to meet each of you, not as an integrationist or a civil-rights leader but as a fellow clergyman and a Christian brother. Let us all hope that the dark clouds of racial prejudice will soon pass away and the deep fog of misunderstanding will be lifted from our fear drenched communities, and in some not too distant tomorrow the radiant stars of love and brotherhood will shine over our great nation with all their scintillating beauty.”

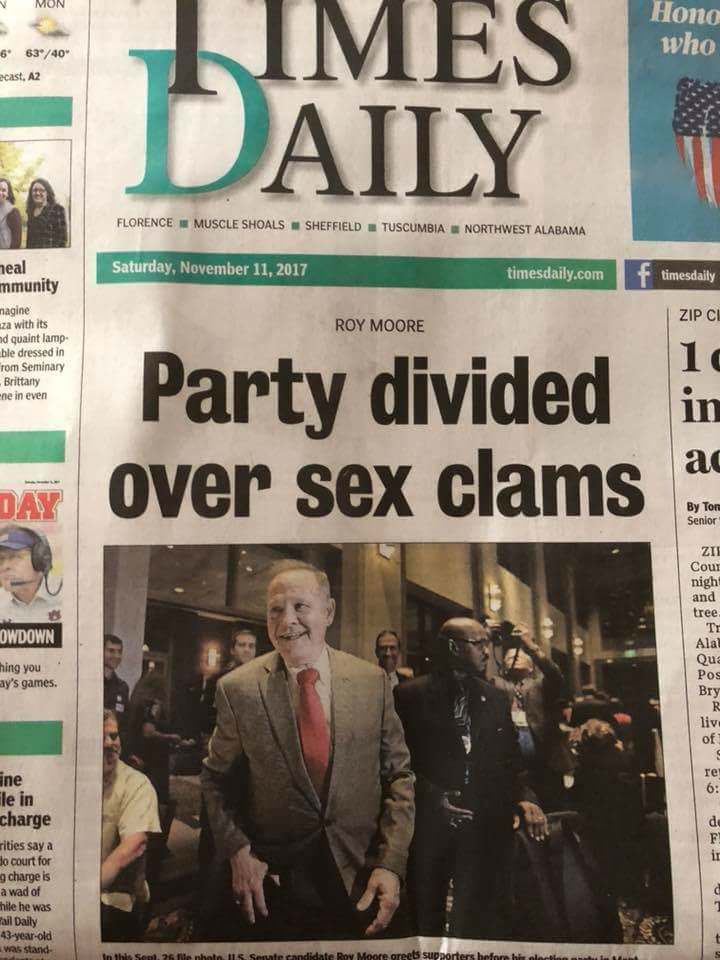

I rather doubt that the Clemson football team was having babies, but….

I rather doubt that the Clemson football team was having babies, but….

The one thing you need to know about me as I tell this story is that I’m an insulin-dependent diabetic.

The one thing you need to know about me as I tell this story is that I’m an insulin-dependent diabetic.