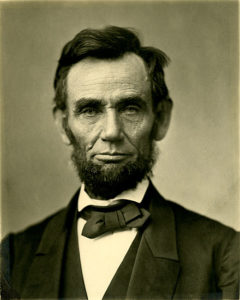

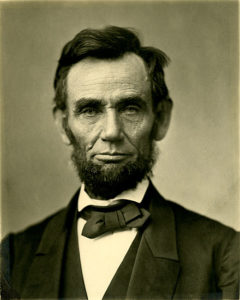

Fake quotes, especially fake Abraham Lincoln quotes, are a popular thing online. Just this week, the Republican National Committee got caught out with one in a tweet celebrating Lincoln’s birthday that read:

Fake quotes, especially fake Abraham Lincoln quotes, are a popular thing online. Just this week, the Republican National Committee got caught out with one in a tweet celebrating Lincoln’s birthday that read:

“And in the end, it’s not the years in your life that count, it’s the life in your years.”

Hmmff, doesn’t even sound like Lincoln – probably because, as the NY Times reports, it likely came from a 1947 advertisement for a book on aging.

The problem of online fake quotes is certainly not limited to fans of our 16th president, however, as I pointed out in a commentary I wrote for the late Charleston Daily Mail back in February of 2007. Here’s the story, along with a few updates:

America is Great Because Lincoln Hanged Congressmen: Quotes That Aren’t Quotes

By Ralph E. Hanson

February 2007

Charleston Daily Mail

There’s been a popular quote by President Abraham Lincoln making the rounds lately. It goes something like this:

Congressmen who willfully take actions during wartime that damage morale and undermine the military are saboteurs and should be arrested, exiled, or hanged.

There’s only one thing wrong with it as a quote: Lincoln didn’t say it — either directly or indirectly.

As was pointed out last August by FactCheck.org, a non-partisan “consumer advocate” web site run by the Annenberg Public Policy Center of the University of Pennsylvania, the quote actually comes from an article written by conservative scholar J. Michael Waller published in the now defunct magazine Insight. Waller claims that the quote marks around the opening statement in his article were inserted by a confused copy editor.

Despite the debunking last summer, the quote has found new life on the Internet, in a recent column from the Washington Times, and in a speech by Rep. Don Young (R-Alaska) supporting the “surge” of troops in Iraq. Seems that there’s a lot of folks who are amused by the thought of executing anyone who disagrees with the president.

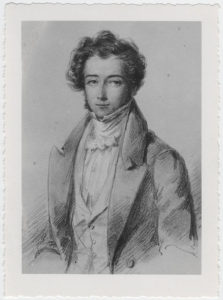

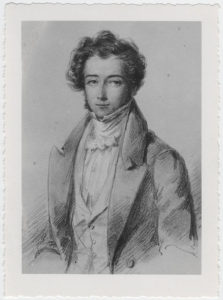

Of course, the Lincoln comment isn’t the only faux 19th century quote that’s made the round in recent years. Alexis de Tocqueville was a young French aristocrat who toured the United States starting in 1831. He wrote about his experiences in the two-volume book Democracy in America; a book that’s become the definitive source of inspirational quotes about America.

Of course, the Lincoln comment isn’t the only faux 19th century quote that’s made the round in recent years. Alexis de Tocqueville was a young French aristocrat who toured the United States starting in 1831. He wrote about his experiences in the two-volume book Democracy in America; a book that’s become the definitive source of inspirational quotes about America.

In fact, comments about the book and de Tocqueville were so prevalent on C-SPAN in the 1990s, that founder Brian Lamb had the public affairs network spend more than a year following de Tocqueville’s travels around the country. (Update: I just did a search on C-SPAN’s website and found more than 1,200 references to de Tocqueville.)

But there was one de Tocqueville quote that kept showing up again and again in political speeches:

I sought for the greatness and genius of America in her commodious harbors and her ample rivers – and it was not there . . . in her fertile fields and boundless forests and it was not there . . . in her rich mines and her vast world commerce – and it was not there . . . in her democratic Congress and her matchless Constitution – and it was not there. Not until I went into the churches of America and heard her pulpits flame with righteousness did I understand the secret of her genius and power. America is great because she is good, and if America ever ceases to be good, she will cease to be great.

(Update: Here’s a link to a speech by Jack Kemp where he gives the faux de Tocqueville quote at about the 9 minute point. At the time I checked, however, the audio was echoing on this recording.)

Dr. John J. Pitney, Jr., a professor of government at Claremont McKenna College, had his students try to locate the source of this commonly used quote. The only problem was that it never showed up in any of de Tocqueville’s books or letters.

It turns out, Pitney writes in The Weekly Standard, that the quote comes from a 1952 speech written for President Eisenhower. The writer most likely drew the quote from a 1941 book on religion and the American dream. (Eisenhower, by the way, attributed the quote not to de Tocqueville but rather to a “wise philosopher who came to this country.”)

The quote has since been used in one form or another by presidents and presidential candidates Ronald Reagan, Bill Clinton, Ross Perot, Pat Buchanan, and Phil Gramm. (Update: Told you this wasn’t a partisan thing – Republicans, Democrats, and Independents!)

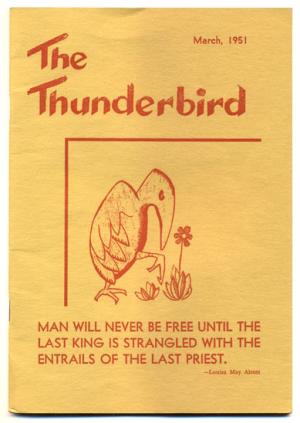

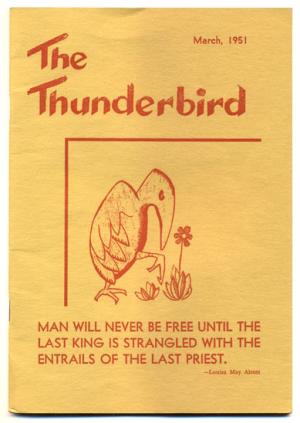

Neither of these manufactured quotes is as much fun, however, as the one that got Pennsylvania-born writer Edward Abbey fired as the editor of the University of New Mexico’s literary journal.

Neither of these manufactured quotes is as much fun, however, as the one that got Pennsylvania-born writer Edward Abbey fired as the editor of the University of New Mexico’s literary journal.

On the cover of the magazine he printed the Voltaire quote “Man will never be free until the last king is strangled with the entrails of the last priest,” but he attributed it to Louisa May Alcott.

(Update: I was myself guilty of perpetrating a small bit of false quoting here. I had read that the “entrails” quote was from Voltaire, but if he said it, he was likely quoting from 18th century philosopher Denis Diderot.)

Fake quotes, especially fake Abraham Lincoln quotes, are a popular thing online. Just this week, the

Fake quotes, especially fake Abraham Lincoln quotes, are a popular thing online. Just this week, the  Of course, the Lincoln comment isn’t the only faux 19th century quote that’s made the round in recent years. Alexis de Tocqueville was a young French aristocrat who toured the United States starting in 1831. He wrote about his experiences in the two-volume book Democracy in America; a book that’s become the definitive source of inspirational quotes about America.

Of course, the Lincoln comment isn’t the only faux 19th century quote that’s made the round in recent years. Alexis de Tocqueville was a young French aristocrat who toured the United States starting in 1831. He wrote about his experiences in the two-volume book Democracy in America; a book that’s become the definitive source of inspirational quotes about America.

How it is: In November of 2017, Playboy announced that it was returning to publishing photos of nude women. Though they wouldn’t be quite as nude as they had been in the past. Cooper Hefner, the magazine’s creative officer and son of the magazine’s founder, tweeted Monday, “I’ll be the first to admit the way in which the magazine portrayed nudity was dated, but removing it entirely was a mistake.” The New York Post reports, “The new issue displays breasts and butts, but not full frontal nudity that had typified the earlier incarnation before the switch with the March issue a full year earlier.” So now you know.

How it is: In November of 2017, Playboy announced that it was returning to publishing photos of nude women. Though they wouldn’t be quite as nude as they had been in the past. Cooper Hefner, the magazine’s creative officer and son of the magazine’s founder, tweeted Monday, “I’ll be the first to admit the way in which the magazine portrayed nudity was dated, but removing it entirely was a mistake.” The New York Post reports, “The new issue displays breasts and butts, but not full frontal nudity that had typified the earlier incarnation before the switch with the March issue a full year earlier.” So now you know.